Excited to share my journey of creating HYPER-PERSONALIZED graphs of reasoning and chain of thought PROMPTS for LLMs that began 10 years ago before it was a “thing.” Check out this video to learn more about my passion for this innovative approach:

Excited to share my journey of creating HYPER-PERSONALIZED graphs of reasoning and chain of thought PROMPTS for LLMs that began 10 years ago before it was a “thing.” Check out this video to learn more about my passion for this innovative approach:

Phil and Pam, as the Context Couple, will start a serieis of short vlogs where they will explain and show what contextual reasoning is and more importantlhy, how to develop and practice this essential life skill.

And they will explain and show how, by using contextual reasoning as a base, humans and AI can collaborate.

Please follow us on this exciting journey.

Navigating the Cognitive Age—a remarkable leap in human capability and understanding enabled by artificial intelligence. •

🤖I’m concerned that people are completely replacing THINKING with PROMPTING. What’s left is an empty-headed techno zombie commanded by its AI overlord.

The magic of the prompt is the dynamic interplay between humans and tech—in the context of a Socratic dialogue.”

As we wrote the day we started this blog in May of 2014, “This will require imprinting AI’s genome with social intelligence for human interaction. It will require wisdom-powered coding. It must begin right now.” https://www.socializingai.com/point/

We must move far beyond current AI/LLM prompts, to hyper-personalized situation specific individual prompts.

… as Beijing began to build up speed, the United States government was slowing to a walk. After President Trump took office, the Obama-era reports on AI were relegated to an archived website.

… as Beijing began to build up speed, the United States government was slowing to a walk. After President Trump took office, the Obama-era reports on AI were relegated to an archived website.

In March 2017, Treasury secretary Steven Mnuchin said that the idea of humans losing jobs because of AI “is not even on our radar screen.” It might be a threat, he added, in “50 to 100 more years.” That same year, China committed itself to building a $150 billion AI industry by 2030.

And what’s at stake is not just the technological dominance of the United States. At a moment of great anxiety about the state of modern liberal democracy, AI in China appears to be an incredibly powerful enabler of authoritarian rule. Is the arc of the digital revolution bending toward tyranny, and is there any way to stop it?

AFTER THE END of the Cold War, conventional wisdom in the West came to be guided by two articles of faith: that liberal democracy was destined to spread across the planet, and that digital technology would be the wind at its back.

As the era of social media kicked in, the techno-optimists’ twin articles of faith looked unassailable. In 2009, during Iran’s Green Revolution, outsiders marveled at how protest organizers on Twitter circumvented the state’s media blackout. A year later, the Arab Spring toppled regimes in Tunisia and Egypt and sparked protests across the Middle East, spreading with all the virality of a social media phenomenon—because, in large part, that’s what it was.

“If you want to liberate a society, all you need is the internet,” said Wael Ghonim, an Egyptian Google executive who set up the primary Facebook group that helped galvanize dissenters in Cairo.

It didn’t take long, however, for the Arab Spring to turn into winter

…. in 2013 the military staged a successful coup. Soon thereafter, Ghonim moved to California, where he tried to set up a social media platform that would favor reason over outrage. But it was too hard to peel users away from Twitter and Facebook, and the project didn’t last long. Egypt’s military government, meanwhile, recently passed a law that allows it to wipe its critics off social media.

Of course, it’s not just in Egypt and the Middle East that things have gone sour. In a remarkably short time, the exuberance surrounding the spread of liberalism and technology has turned into a crisis of faith in both. Overall, the number of liberal democracies in the world has been in steady decline for a decade. According to Freedom House, 71 countries last year saw declines in their political rights and freedoms; only 35 saw improvements.

While the crisis of democracy has many causes, social media platforms have come to seem like a prime culprit.

Which leaves us where we are now: Rather than cheering for the way social platforms spread democracy, we are busy assessing the extent to which they corrode it.

VLADIMIR PUTIN IS a technological pioneer when it comes to cyberwarfare and disinformation. And he has an opinion about what happens next with AI: “The one who becomes the leader in this sphere will be the ruler of the world.”

It’s not hard to see the appeal for much of the world of hitching their future to China. Today, as the West grapples with stagnant wage growth and declining trust in core institutions, more Chinese people live in cities, work in middle-class jobs, drive cars, and take vacations than ever before. China’s plans for a tech-driven, privacy-invading social credit system may sound dystopian to Western ears, but it hasn’t raised much protest there.

In a recent survey by the public relations consultancy Edelman, 84 percent of Chinese respondents said they had trust in their government. In the US, only a third of people felt that way.

… for now, at least, conflicting goals, mutual suspicion, and a growing conviction that AI and other advanced technologies are a winner-take-all game are pushing the two countries’ tech sectors further apart.

A permanent cleavage will come at a steep cost and will only give techno-authoritarianism more room to grow.

Source: Wired (click to read the full article)

Coding must mean consciously grappling with ethical choices in addition to architecting systems that respect core human rights like privacy, he suggested.

Coding must mean consciously grappling with ethical choices in addition to architecting systems that respect core human rights like privacy, he suggested.

“Ethics, like technology, is design,”

“As we’re designing the system, we’re designing society. Ethical rules that we choose to put in that design [impact the society]… Nothing is self evident. Everything has to be put out there as something that we think we will be a good idea as a component of our society.”

If your tech philosophy is the equivalent of ‘move fast and break things’ it’s a failure of both imagination and innovation to not also keep rethinking policies and terms of service — “to a certain extent from scratch” — to account for fresh social impacts, he argued in the speech.

He described today’s digital platforms as “sociotechnical systems” — meaning “it’s not just about the technology when you click on the link it is about the motivation someone has to make such a great thing because then they are read and the excitement they get just knowing that other people are reading the things that they have written”.

“We must consciously decide on both of these, both the social side and the technical side,”

“[These platforms are] anthropogenic, made by people … Facebook and Twitter are anthropogenic. They’re made by people. They’ve coded by people. And the people who code them are constantly trying to figure out how to make them better.”

Source: Techcrunch

“Fifteen years ago, when we were coming here to Austin to talk about the internet, it was this magical place that was different from the rest of the world,” said Ev Williams, now the CEO of Medium, at a panel over the weekend.

“Fifteen years ago, when we were coming here to Austin to talk about the internet, it was this magical place that was different from the rest of the world,” said Ev Williams, now the CEO of Medium, at a panel over the weekend.

“It was a subset” of the general population, he said, “and everyone was cool. There were some spammers, but that was kind of it. And now it just reflects the world.” He continued: “When we built Twitter, we weren’t thinking about these things. We laid down fundamental architectures that had assumptions that didn’t account for bad behavior. And now we’re catching on to that.”

Questions about the unintended consequences of social networks pervaded this year’s event. Academics, business leaders, and Facebook executives weighed in on how social platforms spread misinformation, encourage polarization, and promote hate speech.

The idea that the architects of our social networks would face their comeuppance in Austin was once all but unimaginable at SXSW, which is credited with launching Twitter, Foursquare, and Meerkat to prominence.

But this year, the festival’s focus turned to what social apps had wrought — to what Chris Zappone, a who covers Russian influence campaigns at Australian newspaper The Age, called at his panel “essentially a national emergency.”

Steve Huffman, the CEO of Reddit discouraged strong intervention from the government. “The foundation of the United States and the First Amendment is really solid,” Huffman said. “We’re going through a very difficult time. And as I mentioned before, our values are being tested. But that’s how you know they’re values. It’s very important that we stand by our values and don’t try to overcorrect.”

Sen. Mark Warner (D-VA), vice chairman of the Senate Select Committee on intelligence, echoed that sentiment. “We’re going to need their cooperation because if not, and you simply leave this to Washington, we’ll probably mess it up,” he said at a panel that, he noted with great disappointment, took place in a room that was more than half empty. “It needs to be more of a collaborative process. But the notion that this is going to go away just isn’t accurate.”

Nearly everyone I heard speak on the subject of propaganda this week said something like “there are no easy answers” to the information crisis.

And if there is one thing that hasn’t changed about SXSW, it was that: a sense that tech would prevail in the end.

“It would also be naive to say we can’t do anything about it,” Ev Williams said. “We’re just in the early days of trying to do something about it.”

Source: The Verge – Casey Newton

In the hours since the news of his death broke, fans have been resurfacing some of their favorite quotes of his, including those from his Reddit AMA two years ago.

He wrote confidently about the imminent development of human-level AI and warned people to prepare for its consequences:

“When it eventually does occur, it’s likely to be either the best or worst thing ever to happen to humanity, so there’s huge value in getting it right.”

When asked if human-created AI could exceed our own intelligence, he replied:

It’s clearly possible for a something to acquire higher intelligence than its ancestors: we evolved to be smarter than our ape-like ancestors, and Einstein was smarter than his parents. The line you ask about is where an AI becomes better than humans at AI design, so that it can recursively improve itself without human help. If this happens, we may face an intelligence explosion that ultimately results in machines whose intelligence exceeds ours by more than ours exceeds that of snails.

As for whether that same AI could potentially be a threat to humans one day?

“AI will probably develop a drive to survive and acquire more resources as a step toward accomplishing whatever goal it has, because surviving and having more resources will increase its chances of accomplishing that other goal,” he wrote. “This can cause problems for humans whose resources get taken away.”

Source: Cosmopolitan

In the forward to Microsoft’s recent book, The Future Computed, executives Brad Smith and Harry Shum proposed that Artificial Intelligence (AI) practitioners highlight their ethical commitments by taking an oath analogous to the Hippocratic Oath sworn by doctors for generations.

In the past, much power and responsibility over life and death was concentrated in the hands of doctors.

Now, this ethical burden is increasingly shared by the builders of AI software.

Future AI advances in medicine, transportation, manufacturing, robotics, simulation, augmented reality, virtual reality, military applications, dictate that AI be developed from a higher moral ground today.

In response, I (Oren Etzioni) edited the modern version of the medical oath to address the key ethical challenges that AI researchers and engineers face …

The oath is as follows:

I swear to fulfill, to the best of my ability and judgment, this covenant:

I will respect the hard-won scientific gains of those scientists and engineers in whose steps I walk, and gladly share such knowledge as is mine with those who are to follow.

I will apply, for the benefit of the humanity, all measures required, avoiding those twin traps of over-optimism and uniformed pessimism.

I will remember that there is an art to AI as well as science, and that human concerns outweigh technological ones.

Most especially must I tread with care in matters of life and death. If it is given me to save a life using AI, all thanks. But it may also be within AI’s power to take a life; this awesome responsibility must be faced with great humbleness and awareness of my own frailty and the limitations of AI. Above all, I must not play at God nor let my technology do so.

I will respect the privacy of humans for their personal data are not disclosed to AI systems so that the world may know.

I will consider the impact of my work on fairness both in perpetuating historical biases, which is caused by the blind extrapolation from past data to future predictions, and in creating new conditions that increase economic or other inequality.

My AI will prevent harm whenever it can, for prevention is preferable to cure.

My AI will seek to collaborate with people for the greater good, rather than usurp the human role and supplant them.

I will remember that I am not encountering dry data, mere zeros and ones, but human beings, whose interactions with my AI software may affect the person’s freedom, family, or economic stability. My responsibility includes these related problems.

I will remember that I remain a member of society, with special obligations to all my fellow human beings.

Source: TechCrunch – Oren Etzioni

For a field that was not well known outside of academia a decade ago, artificial intelligence has grown dizzyingly fast.

Tech companies from Silicon Valley to Beijing are betting everything on it, venture capitalists are pouring billions into research and development, and start-ups are being created on what seems like a daily basis. If our era is the next Industrial Revolution, as many claim, A.I. is surely one of its driving forces.

I worry, however, that enthusiasm for A.I. is preventing us from reckoning with its looming effects on society. Despite its name, there is nothing “artificial” about this technology — it is made by humans, intended to behave like humans and affects humans. So if we want it to play a positive role in tomorrow’s world, it must be guided by human concerns.

I call this approach “human-centered A.I.” It consists of three goals that can help responsibly guide the development of intelligent machines.

No technology is more reflective of its creators than A.I. It has been said that there are no “machine” values at all, in fact; machine values are human values.

A human-centered approach to A.I. means these machines don’t have to be our competitors, but partners in securing our well-being. However autonomous our technology becomes, its impact on the world — for better or worse — will always be our responsibility.

Fei-Fei Li is a professor of computer science at Stanford, where she directs the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Lab, and the chief scientist for A.I. research at Google Cloud.

Source: NYT

Belgian Ian Frejean, 11, walks with “Zora” the robot, a humanoid robot designed to entertain patients and to support care providers, at AZ Damiaan hospital in Ostend, Belgium

As autonomous and intelligent systems become more and more ubiquitous and sophisticated, developers and users face an important question:

How do we ensure that when these technologies are in a position to make a decision, they make the right decision — the ethically right decision?

It’s a complicated question. And there’s not one single right answer.

But there is one thing that people who work in the budding field of AI ethics seem to agree on.

“I think there is a domination of Western philosophy, so to speak, in AI ethics,” said Dr. Pak-Hang Wong, who studies Philosophy of Technology and Ethics at the University of Hamburg, in Germany. “By that I mean, when we look at AI ethics, most likely they are appealing to values … in the Western philosophical traditions, such as value of freedom, autonomy and so on.”

Wong is among a group of researchers trying to widen that scope, by looking at how non-Western value systems — including Confucianism, Buddhism and Ubuntu — can influence how autonomous and intelligent designs are developed and how they operate.

“We’re providing standards as a starting place. And then from there, it may be a matter of each tradition, each culture, different governments, establishing their own creation based on the standards that we are providing.”

Jared Bielby, who heads the Classical Ethics committee

Source: PRI

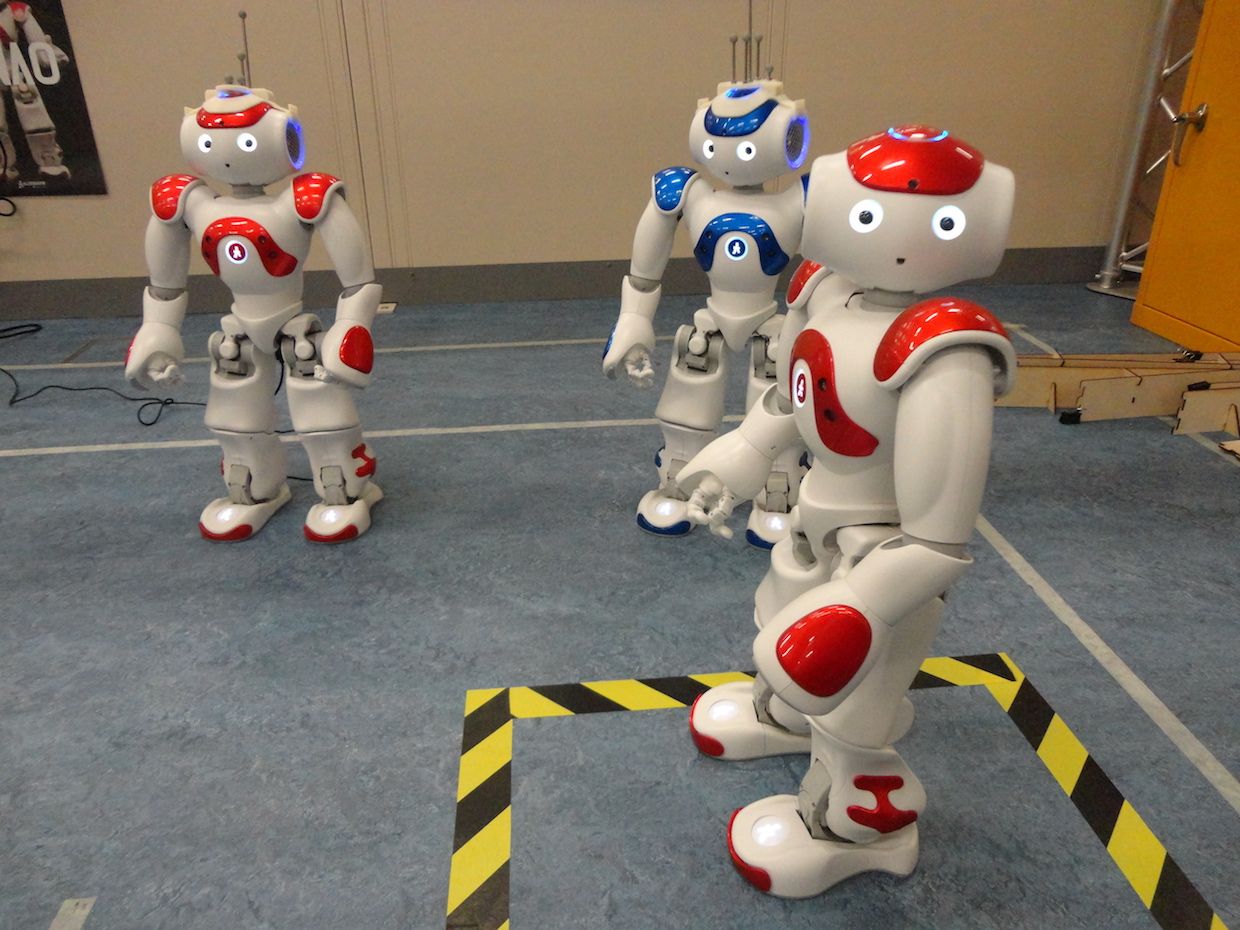

This week my colleague Dieter Vanderelst presented our paper: “The Dark Side of Ethical Robots” at AIES 2018 in New Orleans.

This week my colleague Dieter Vanderelst presented our paper: “The Dark Side of Ethical Robots” at AIES 2018 in New Orleans.

I blogged about Dieter’s very elegant experiment here, but let me summarize. With two NAO robots he set up a demonstration of an ethical robot helping another robot acting as a proxy human, then showed that with a very simple alteration of the ethical robot’s logic it is transformed into a distinctly unethical robot—behaving either competitively or aggressively toward the proxy human.

Here are our paper’s key conclusions:

The ease of transformation from ethical to unethical robot is hardly surprising. It is a straightforward consequence of the fact that both ethical and unethical behaviors require the same cognitive machinery with—in our implementation—only a subtle difference in the way a single value is calculated. In fact, the difference between an ethical (i.e. seeking the most desirable outcomes for the human) robot and an aggressive (i.e. seeking the least desirable outcomes for the human) robot is a simple negation of this value.

Let us examine the risks associated with ethical robots and if, and how, they might be mitigated. There are three.

It is very clear that guaranteeing the security of ethical robots is beyond the scope of engineering and will need regulatory and legislative efforts.

Considering the ethical, legal and societal implications of robots, it becomes obvious that robots themselves are not where responsibility lies. Robots are simply smart machines of various kinds and the responsibility to ensure they behave well must always lie with human beings. In other words, we require ethical governance, and this is equally true for robots with or without explicit ethical behaviors.

Two years ago I thought the benefits of ethical robots outweighed the risks. Now I’m not so sure.

I now believe that – even with strong ethical governance—the risks that a robot’s ethics might be compromised by unscrupulous actors are so great as to raise very serious doubts over the wisdom of embedding ethical decision making in real-world safety critical robots, such as driverless cars. Ethical robots might not be such a good idea after all.

Thus, even though we’re calling into question the wisdom of explicitly ethical robots, that doesn’t change the fact that we absolutely must design all robots to minimize the likelihood of ethical harms, in other words we should be designing implicitly ethical robots within Moor’s schema.

Source: IEEE

Jim Steyer, left, and Tristan Harris in Common Sense’s headquarters. Common Sense is helping fund the The Truth About Tech campaign. Peter Prato for The New York Times

A group of Silicon Valley technologists who were early employees at Facebook and Google, alarmed over the ill effects of social networks and smartphones, are banding togethe to challenge the companies they helped build.

The cohort is creating a union of concerned experts called the Center for Humane Technology. Along with the nonprofit media watchdog group Common Sense Media, it also plans an anti-tech addiction lobbying effort and an ad campaign at 55,000 public schools in the United States.

The campaign, titled The Truth About Tech

“We were on the inside,” said Tristan Harris, a former in-house ethicist at Google who is heading the new group. “We know what the companies measure. We know how they talk, and we know how the engineering works.”

An unprecedented alliance of former employees of some of today’s biggest tech companies. Apart from Mr. Harris, the center includes Sandy Parakilas, a former Facebook operations manager; Lynn Fox, a former Apple and Google communications executive; Dave Morin, a former Facebook executive; Justin Rosenstein, who created Facebook’s Like button and is a co-founder of Asana; Roger McNamee, an early investor in Facebook; and Renée DiResta, technologist who studies bots.

“Facebook appeals to your lizard brain — primarily fear and anger. And with smartphones, they’ve got you for every waking moment. This is an opportunity for me to correct a wrong.” Roger McNamee, an early investor in Facebook

Source: NYT

Google CEO Sundar Pichai believes artificial intelligence could have “more profound” implications for humanity than electricity or fire, according to recent comments.

Google CEO Sundar Pichai believes artificial intelligence could have “more profound” implications for humanity than electricity or fire, according to recent comments.

Pichai also warned that the development of artificial intelligence could pose as much risk as that of fire if its potential is not harnessed correctly.

“AI is one of the most important things humanity is working on” Pichai said in an interview with MSNBC and Recode

“My point is AI is really important, but we have to be concerned about it,” Pichai said. “It’s fair to be worried about it—I wouldn’t say we’re just being optimistic about it— we want to be thoughtful about it. AI holds the potential for some of the biggest advances we’re going to see.”

Source: Newsweek

Humanity faces a wide range of challenges that are characterised by extreme complexity

… the successful integration of AI technologies into our social and economic world creates its own challenges. They could either help overcome economic inequality or they could worsen it if the benefits are not distributed widely.

They could shine a light on damaging human biases and help society address them, or entrench patterns of discrimination and perpetuate them. Getting things right requires serious research into the social consequences of AI and the creation of partnerships to ensure it works for the public good.

This is why I predict the study of the ethics, safety and societal impact of AI is going to become one of the most pressing areas of enquiry over the coming year.

It won’t be easy: the technology sector often falls into reductionist ways of thinking, replacing complex value judgments with a focus on simple metrics that can be tracked and optimised over time.

There has already been valuable work done in this area. For example, there is an emerging consensus that it is the responsibility of those developing new technologies to help address the effects of inequality, injustice and bias. In 2018, we’re going to see many more groups start to address these issues.

Of course, it’s far simpler to count likes than to understand what it actually means to be liked and the effect this has on confidence or self-esteem.

Progress in this area also requires the creation of new mechanisms for decision-making and voicing that include the public directly. This would be a radical change for a sector that has often preferred to resolve problems unilaterally – or leave others to deal with them.

We need to do the hard, practical and messy work of finding out what ethical AI really means. If we manage to get AI to work for people and the planet, then the effects could be transformational. Right now, there’s everything to play for.

Source: Wired

You see a man walking toward you on the street. He reminds you of someone from long ago. Such as a high school classmate, who belonged to the football team? Wasn’t a great player but you were fond of him then. You don’t recall him attending fifth, 10th and 20th reunions. He must have moved away and established his life there and cut off his ties to his friends here.

You look at his face and you really can’t tell if it’s Bob for sure. You had forgotten many of his key features and this man seems to have gained some weight.

The distance between the two of you is quickly closing and your mind is running at full speed trying to decide if it is Bob.

At this moment, you have a few choices. A decision tree will emerge and you will need to choose one of the available options.

In the logic diagram I show, there are some question that is influenced by the emotion. B2) “Nah, let’s forget it” and C) and D) are results of emotional decisions and have little to do with fact this may be Bob or not.

The human decision-making process is often influenced by emotion, which is often independent of fact.

You decision to drop the idea of meeting Bob after so many years is caused by shyness, laziness and/or avoiding some embarrassment in case this man is not Bob. The more you think about this decision-making process, less sure you’d become. After all, if you and Bob hadn’t spoken for 20 years, maybe we should leave the whole thing alone.

Thus, this is clearly the result of human intelligence working.

If this were artificial intelligence, chances are decisions B2, C and D wouldn’t happen. Machines today at their infantile stage of development do not know such emotional feeling as “too much trouble,” hesitation due to fear of failing (Bob says he isn’t Bob), or laziness and or “too complicated.” In some distant time, these complex feelings and deeds driven by the emotion would be realized, I hope. But, not now.

At this point of the state of art of AI, a machine would not hesitate once it makes a decision. That’s because it cannot hesitate. Hesitation is a complex emotional decision that a machine simply cannot perform.

There you see a huge crevice between the human intelligence and AI.

In fact, animals (remember we are also an animal) display complex emotional decisions daily. Now, are you getting some feeling about human intelligence and AI?

Source: Fosters.com

Shintaro “Sam” Asano was named by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2011 as one of the 10 most influential inventors of the 20th century who improved our lives. He is a businessman and inventor in the field of electronics and mechanical systems who is credited as the inventor of the portable fax machine.

Shintaro “Sam” Asano was named by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2011 as one of the 10 most influential inventors of the 20th century who improved our lives. He is a businessman and inventor in the field of electronics and mechanical systems who is credited as the inventor of the portable fax machine.

A few highlights from THE BUSINESS INSIDER INTERVIEW with Jaron

A few highlights from THE BUSINESS INSIDER INTERVIEW with Jaron

But that general principle — that we’re not treating people well enough with digital systems — still bothers me. I do still think that is very true.

—

Well, this is maybe the greatest tragedy in the history of computing, and it goes like this: there was a well-intentioned, sweet movement in the ‘80s to try to make everything online free. And it started with free software and then it was free music, free news, and other free services.

But, at the same time, it’s not like people were clamoring for the government to do it or some sort of socialist solution. If you say, well, we want to have entrepreneurship and capitalism, but we also want it to be free, those two things are somewhat in conflict, and there’s only one way to bridge that gap, and it’s through the advertising model.

And advertising became the model of online information, which is kind of crazy. But here’s the problem: if you start out with advertising, if you start out by saying what I’m going to do is place an ad for a car or whatever, gradually, not because of any evil plan — just because they’re trying to make their algorithms work as well as possible and maximize their shareholders value and because computers are getting faster and faster and more effective algorithms —

what starts out as advertising morphs into behavior modification.

A second issue is that people who participate in a system of this time, since everything is free since it’s all being monetized, what reward can you get? Ultimately, this system creates assholes, because if being an asshole gets you attention, that’s exactly what you’re going to do. Because there’s a bias for negative emotions to work better in engagement, because the attention economy brings out the asshole in a lot of other people, the people who want to disrupt and destroy get a lot more efficiency for their spend than the people who might be trying to build up and preserve and improve.

—

Q: What do you think about programmers using consciously addicting techniques to keep people hooked to their products?

A: There’s a long and interesting history that goes back to the 19th century, with the science of Behaviorism that arose to study living things as though they were machines.

Behaviorists had this feeling that I think might be a little like this godlike feeling that overcomes some hackers these days, where they feel totally godlike as though they have the keys to everything and can control people

—

I think our responsibility as engineers is to engineer as well as possible, and to engineer as well as possible, you have to treat the thing you’re engineering as a product.

You can’t respect it in a deified way.

It goes in the reverse. We’ve been talking about the behaviorist approach to people, and manipulating people with addictive loops as we currently do with online systems.

In this case, you’re treating people as objects.

It’s the flipside of treating machines as people, as AI does. They go together. Both of them are mistakes

Source: Read the extensive interview at Business Insider

As autonomous and intelligent systems become more pervasive, it is essential the designers and developers behind them stop to consider the ethical considerations of what they are unleashing.

As autonomous and intelligent systems become more pervasive, it is essential the designers and developers behind them stop to consider the ethical considerations of what they are unleashing.

That’s the view of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) which this week released for feedback its second Ethically Aligned Design document in an attempt

to ensure such systems “remain human-centric”.

“These systems have to behave in a way that is beneficial to people beyond reaching functional goals and addressing technical problems. This will allow for an elevated level of trust between people and technology that is needed for its fruitful, pervasive use in our daily lives,” the document states.

“Defining what exactly ‘right’ and ‘good’ are in a digital future is a question of great complexity that places us at the intersection of technology and ethics,”

“Throwing our hands up in air crying ‘it’s too hard’ while we sit back and watch technology careen us forward into a future that happens to us, rather than one we create, is hardly a viable option.

“This publication is a truly game-changing and promising first step in a direction – which has often felt long in coming – toward breaking the protective wall of specialisation that has allowed technologists to disassociate from the societal impacts of their technologies.”

“It will demand that future tech leaders begin to take responsibility for and think deeply about the non-technical impact on disempowered groups, on privacy and justice, on physical and mental health, right down to unpacking hidden biases and moral implications. It represents a positive step toward ensuring the technology we build as humans genuinely benefits us and our planet,” [University of Sydney software engineering Professor Rafael Calvo.]

“We believe explicitly aligning technology with ethical values will help advance innovation with these new tools while diminishing fear in the process” the IEEE said.

Source: Computer World

This article attempts to bring our readers to Kate’s brilliant Keynote speech at NIPS 2017. It talks about different forms of bias in Machine Learning systems and the ways to tackle such problems.

This article attempts to bring our readers to Kate’s brilliant Keynote speech at NIPS 2017. It talks about different forms of bias in Machine Learning systems and the ways to tackle such problems.

The rise of Machine Learning is every bit as far reaching as the rise of computing itself.

A vast new ecosystem of techniques and infrastructure are emerging in the field of machine learning and we are just beginning to learn their full capabilities. But with the exciting things that people can do, there are some really concerning problems arising.

Forms of bias, stereotyping and unfair determination are being found in machine vision systems, object recognition models, and in natural language processing and word embeddings. High profile news stories about bias have been on the rise, from women being less likely to be shown high paying jobs to gender bias and object recognition datasets like MS COCO, to racial disparities in education AI systems.

Bias is a skew that produces a type of harm.

Commonly from Training data. It can be incomplete, biased or otherwise skewed. It can draw from non-representative samples that are wholly defined before use. Sometimes it is not obvious because it was constructed in a non-transparent way. In addition to human labeling, other ways that human biases and cultural assumptions can creep in ending up in exclusion or overrepresentation of subpopulation. Case in point: stop-and-frisk program data used as training data by an ML system. This dataset was biased due to systemic racial discrimination in policing.

Majority of the literature understand bias as harms of allocation. Allocative harm is when a system allocates or withholds certain groups, an opportunity or resource. It is an economically oriented view primarily. Eg: who gets a mortgage, loan etc.

Allocation is immediate, it is a time-bound moment of decision making. It is readily quantifiable. In other words, it raises questions of fairness and justice in discrete and specific transactions.

It gets tricky when it comes to systems that represent society but don’t allocate resources. These are representational harms. When systems reinforce the subordination of certain groups along the lines of identity like race, class, gender etc.

It is a long-term process that affects attitudes and beliefs. It is harder to formalize and track. It is a diffused depiction of humans and society. It is at the root of all of the other forms of allocative harm.

The ultimate question for fairness in machine learning is this.

Who is going to benefit from the system we are building? And who might be harmed?

Source: Datahub

Kate Crawford is a Principal Researcher at Microsoft Research and a Distinguished Research Professor at New York University. She has spent the last decade studying the social implications of data systems, machine learning, and artificial intelligence. Her recent publications address data bias and fairness, and social impacts of artificial intelligence among others.

Chamath Palihapitiya speaks at a Vanity Fair event in October 2016. Photo by Mike Windle/Getty Images for Vanity Fair

![]() Chamath Palihapitiya, who joined Facebook in 2007 and became its vice president for user growth, said he feels “tremendous guilt” about the company he helped make.

Chamath Palihapitiya, who joined Facebook in 2007 and became its vice president for user growth, said he feels “tremendous guilt” about the company he helped make.

“I think we have created tools that are ripping apart the social fabric of how society works”

Palihapitiya’s criticisms were aimed not only at Facebook, but the wider online ecosystem.

“The short-term, dopamine-driven feedback loops we’ve created are destroying how society works,” he said, referring to online interactions driven by “hearts, likes, thumbs-up.” “No civil discourse, no cooperation; misinformation, mistruth. And it’s not an American problem — this is not about Russians ads. This is a global problem.”

He went on to describe an incident in India where hoax messages about kidnappings shared on WhatsApp led to the lynching of seven innocent people.

“That’s what we’re dealing with,” said Palihapitiya. “And imagine taking that to the extreme, where bad actors can now manipulate large swathes of people to do anything you want. It’s just a really, really bad state of affairs.”

In his talk, Palihapitiya criticized not only Facebook, but Silicon Valley’s entire system of venture capital funding.

He said that investors pump money into “shitty, useless, idiotic companies,” rather than addressing real problems like climate change and disease.

Source: The Verge

UPDATE: FACEBOOK RESPONDS

Chamath has not been at Facebook for over six years. When Chamath was at Facebook we were focused on building new social media experiences and growing Facebook around the world. Facebook was a very different company back then and as we have grown we have realised how our responsibilities have grown too. We take our role very seriously and we are working hard to improve. We’ve done a lot of work and research with outside experts and academics to understand the effects of our service on well-being, and we’re using it to inform our product development. We are also making significant investments more in people, technology and processes, and – as Mark Zuckerberg said on the last earnings call – we are willing to reduce our profitability to make sure the right investments are made.

Source: CNBC

The prestigious Neural Information Processing Systems conference have a new topic on their agenda. Alongside the usual … concern about AI’s power.

The prestigious Neural Information Processing Systems conference have a new topic on their agenda. Alongside the usual … concern about AI’s power.

Kate Crawford … urged attendees to start considering, and finding ways to mitigate, accidental or intentional harms caused by their creations. “

“Amongst the very real excitement about what we can do there are also some really concerning problems arising”

“In domains like medicine we can’t have these models just be a black box where something goes in and you get something out but don’t know why,” says Maithra Raghu, a machine-learning researcher at Google. On Monday, she presented open-source software developed with colleagues that can reveal what a machine-learning program is paying attention to in data. It may ultimately allow a doctor to see what part of a scan or patient history led an AI assistant to make a particular diagnosis.

“If you have a diversity of perspectives and background you might be more likely to check for bias against different groups” Hanna Wallach a researcher at Microsoft

Others in Long Beach hope to make the people building AI better reflect humanity. Like computer science as a whole, machine learning skews towards the white, male, and western. A parallel technical conference called Women in Machine Learning has run alongside NIPS for a decade. This Friday sees the first Black in AI workshop, intended to create a dedicated space for people of color in the field to present their work.

Towards the end of her talk Tuesday, Crawford suggested civil disobedience could shape the uses of AI. She talked of French engineer Rene Carmille, who sabotaged tabulating machines used by the Nazis to track French Jews. And she told today’s AI engineers to consider the lines they don’t want their technology to cross. “Are there some things we just shouldn’t build?” she asked.

Source: Wired

[Timnit] Gebru, 34, joined a Microsoft Corp. team called FATE—for Fairness, Accountability, Transparency and Ethics in AI. The program was set up three years ago to ferret out biases that creep into AI data and can skew results.

[Timnit] Gebru, 34, joined a Microsoft Corp. team called FATE—for Fairness, Accountability, Transparency and Ethics in AI. The program was set up three years ago to ferret out biases that creep into AI data and can skew results.

“I started to realize that I have to start thinking about things like bias. Even my own Phd work suffers from whatever issues you’d have with dataset bias.”

Companies, government agencies and hospitals are increasingly turning to machine learning, image recognition and other AI tools to help predict everything from the credit worthiness of a loan applicant to the preferred treatment for a person suffering from cancer. The tools have big blind spots that particularly effect women and minorities.

“The worry is if we don’t get this right, we could be making wrong decisions that have critical consequences to someone’s life, health or financial stability,” says Jeannette Wing, director of Columbia University’s Data Sciences Institute.

AI also has a disconcertingly human habit of amplifying stereotypes. Phd students at the University of Virginia and University of Washington examined a public dataset of photos and found that the images of people cooking were 33 percent more likely to picture women than men. When they ran the images through an AI model, the algorithms said women were 68 percent more likely to appear in the cooking photos.

Researchers say it will probably take years to solve the bias problem.

The good news is that some of the smartest people in the world have turned their brainpower on the problem. “The field really has woken up and you are seeing some of the best computer scientists, often in concert with social scientists, writing great papers on it,” says University of Washington computer science professor Dan Weld. “There’s been a real call to arms.”

Source: Bloomberg

Training an AI platform on social media data, with the intent to reproduce a “human” experience, is fraught with risk. You could liken it to raising a baby on a steady diet of Fox News or CNN, with no input from its parents or social institutions. In either case, you might be breeding a monster.

Training an AI platform on social media data, with the intent to reproduce a “human” experience, is fraught with risk. You could liken it to raising a baby on a steady diet of Fox News or CNN, with no input from its parents or social institutions. In either case, you might be breeding a monster.

Ultimately, social data — alone — represents neither who we actually are nor who we should be. Deeper still, as useful as the social graph can be in providing a training set for AI, what’s missing is a sense of ethics or a moral framework to evaluate all this data. From the spectrum of human experience shared on Twitter, Facebook and other networks, which behaviors should be modeled and which should be avoided? Which actions are right and which are wrong? What’s good … and what’s evil?

Here’s where science comes up short. The answers can’t be gleaned from any social data set. The best analytical tools won’t surface them, no matter how large the sample size.

But they just might be found in the Bible. And the Koran, the Torah, the Bhagavad Gita and the Buddhist Sutras. They’re in the work of Aristotle, Plato, Confucius, Descartes and other philosophers both ancient and modern.

AI, to be effective, needs an ethical underpinning. Data alone isn’t enough. AI needs religion — a code that doesn’t change based on context or training set.

In place of parents and priests, responsibility for this ethical education will increasingly rest on frontline developers and scientists.

As emphasized by leading AI researcher Will Bridewell, it’s critical that future developers are “aware of the ethical status of their work and understand the social implications of what they develop.” He goes so far as to advocate study in Aristotle’s ethics and Buddhist ethics so they can “better track intuitions about moral and ethical behavior.”

On a deeper level, responsibility rests with the organizations that employ these developers, the industries they’re part of, the governments that regulate those industries and — in the end — us.

Source: Recode Ryan Holmes is the founder and CEO of Hootsuite.

Donald Trump meeting PayPal co-founder Peter Thiel and Apple CEO Tim Cook in December last year. Photograph: Evan Vucci/AP

One of the biggest puzzles about our current predicament with fake news and the weaponisation of social media is why the folks who built this technology are so taken aback by what has happened.

We have a burgeoning genre of “OMG, what have we done?” angst coming from former Facebook and Google employees who have begun to realise that the cool stuff they worked on might have had, well, antisocial consequences.

Put simply, what Google and Facebook have built is a pair of amazingly sophisticated, computer-driven engines for extracting users’ personal information and data trails, refining them for sale to advertisers in high-speed data-trading auctions that are entirely unregulated and opaque to everyone except the companies themselves.

The purpose of this infrastructure was to enable companies to target people with carefully customised commercial messages and, as far as we know, they are pretty good at that.

It never seems to have occurred to them that their advertising engines could also be used to deliver precisely targeted ideological and political messages to voters. Hence the obvious question: how could such smart people be so stupid?

My hunch is it has something to do with their educational backgrounds. Take the Google co-founders. Sergey Brin studied mathematics and computer science. His partner, Larry Page, studied engineering and computer science. Zuckerberg dropped out of Harvard, where he was studying psychology and computer science, but seems to have been more interested in the latter.

Now mathematics, engineering and computer science are wonderful disciplines – intellectually demanding and fulfilling. And they are economically vital for any advanced society. But mastering them teaches students very little about society or history – or indeed about human nature.

As a consequence, the new masters of our universe are people who are essentially only half-educated. They have had no exposure to the humanities or the social sciences, the academic disciplines that aim to provide some understanding of how society works, of history and of the roles that beliefs, philosophies, laws, norms, religion and customs play in the evolution of human culture.

We are now beginning to see the consequences of the dominance of this half-educated elite.

Source: The Gaurdian – John Naughton is professor of the public understanding of technology at the Open University.

From left: Twitter’s acting general counsel Sean Edgett, Facebook’s general counsel Colin Stretch and Google’s senior vice president and general counsel Kent Walker, testify before the House Intelligence Committee on Wednesday, Nov. 1, 2017. Manuel Balce Ceneta/AP

Members of Congress confessed how difficult it was for them to even wrap their minds around how today’s Internet works — and can be abused. And for others, the hearings finally drove home the magnitude of the Big Tech platforms.

Sen. John Kennedy, R-La., marveled on Tuesday when Facebook said it could track the source of funding for all 5 million of its monthly advertisers.

“I think you do enormous good, but your power scares me,” he said.

There appears to be no quick patch for the malware afflicting America’s political life.

Over the course of three congressional hearings Tuesday and Wednesday, lawmakers fulminated, Big Tech witnesses were chastened but no decisive action appears to be in store to stop a foreign power from harnessing digital platforms to try to shape the information environment inside the United States.

Legislation offered in the Senate — assuming it passed, months or more from now — would change the calculus slightly: requiring more disclosure and transparency for political ads on Facebook and Twitter and other social platforms.

Even if it became law, however, it would not stop such ads from being sold, nor heal the deep political divisions exploited last year by foreign influence-mongers. The legislation also couldn’t stop a foreign power from using all the other weapons in its arsenal against the U.S., including cyberattacks, the deployment of human spies and others.

“Candidly, your companies know more about Americans, in many ways, than the United States government does. The idea that you had no idea any of this was happening strains my credibility,” Senate Intelligence Committee Vice Chairman Mark Warner, D.-Va.

The companies also made clear they condemn the uses of their services they’ve discovered, which they said violate their policies in many cases.

They also talked more about the scale of the Russian digital operation they’ve uncovered up to this point — which is eye-watering: Facebook general counsel Colin Stretch acknowledged that as many as 150 million Americans may have seen posts or other content linked to Russia’s influence campaign in the 2016 cycle

“There is one thing I’m certain of, and it’s this: Given the complexity of what we have seen, if anyone tells you they have figured it out, they are kidding ourselves. And we can’t afford to kid ourselves about what happened last year — and continues to happen today.” Senate Intelligence Committee Chairman Richard Burr, R-N.C.

Source: NPR

In a statement broadcast live on Facebook on September 21 and subsequently posted to his profile page, Zuckerberg pledged to increase the resources of Facebook’s security and election-integrity teams and to work “proactively to strengthen the democratic process.”

In a statement broadcast live on Facebook on September 21 and subsequently posted to his profile page, Zuckerberg pledged to increase the resources of Facebook’s security and election-integrity teams and to work “proactively to strengthen the democratic process.”

It was an admirable commitment. But reading through it, I kept getting stuck on one line: “We have been working to ensure the integrity of the German elections this weekend,” Zuckerberg writes. It’s a comforting sentence, a statement that shows Zuckerberg and Facebook are eager to restore trust in their system.

But … it’s not the kind of language we expect from media organizations, even the largest ones. It’s the language of governments, or political parties, or NGOs. A private company, working unilaterally to ensure election integrity in a country it’s not even based in?

Facebook has grown so big, and become so totalizing, that we can’t really grasp it all at once.

Like a four-dimensional object, we catch slices of it when it passes through the three-dimensional world we recognize. In one context, it looks and acts like a television broadcaster, but in this other context, an NGO. In a recent essay for the London Review of Books, John Lanchester argued that for all its rhetoric about connecting the world, the company is ultimately built to extract data from users to sell to advertisers. This may be true, but Facebook’s business model tells us only so much about how the network shapes the world.

Between March 23, 2015, when Ted Cruz announced his candidacy, and November 2016, 128 million people in America created nearly 10 billion Facebook posts, shares, likes, and comments about the election. (For scale, 137 million people voted last year.)

In February 2016, the media theorist Clay Shirky wrote about Facebook’s effect: “Reaching and persuading even a fraction of the electorate used to be so daunting that only two national orgs” — the two major national political parties — “could do it. Now dozens can.”

It used to be if you wanted to reach hundreds of millions of voters on the right, you needed to go through the GOP Establishment. But in 2016, the number of registered Republicans was a fraction of the number of daily American Facebook users, and the cost of reaching them directly was negligible.

Tim Wu, the Columbia Law School professor

“Facebook has the same kind of attentional power [as TV networks in the 1950s], but there is not a sense of responsibility,” he said. “No constraints. No regulation. No oversight. Nothing. A bunch of algorithms, basically, designed to give people what they want to hear.”

It tends to get forgotten, but Facebook briefly ran itself in part as a democracy: Between 2009 and 2012, users were given the opportunity to vote on changes to the site’s policy. But voter participation was minuscule, and Facebook felt the scheme “incentivized the quantity of comments over their quality.” In December 2012, that mechanism was abandoned “in favor of a system that leads to more meaningful feedback and engagement.”

Facebook had grown too big, and its users too complacent, for democracy.

Source: NY Magazine

As the director of Stanford’s AI Lab and now as a chief scientist of Google Cloud, Fei-Fei Li is helping to spur the AI revolution. But it’s a revolution that needs to include more people. She spoke with MIT Technology Review senior editor Will Knight about why everyone benefits if we emphasize the human side of the technology.

Why did you join Google?

Researching cutting-edge AI is very satisfying and rewarding, but we’re seeing this great awakening, a great moment in history. For me it’s very important to think about AI’s impact in the world, and one of the most important missions is to democratize this technology. The cloud is this gigantic computing vehicle that delivers computing services to every single industry.

What have you learned so far?

We need to be much more human-centered.

If you look at where we are in AI, I would say it’s the great triumph of pattern recognition. It is very task-focused, it lacks contextual awareness, and it lacks the kind of flexible learning that humans have.

We also want to make technology that makes humans’ lives better, our world safer, our lives more productive and better. All this requires a layer of human-level communication and collaboration.

When you are making a technology this pervasive and this important for humanity, you want it to carry the values of the entire humanity, and serve the needs of the entire humanity.

If the developers of this technology do not represent all walks of life, it is very likely that this will be a biased technology. I say this as a technologist, a researcher, and a mother. And we need to be speaking about this clearly and loudly.

Source: MIT Technology Review

The unit, called DeepMind Ethics and Society, is not the AI Ethics Board that DeepMind was promised when it agreed to be acquired by Google in 2014. That board, which was convened by January 2016, was supposed to oversee all of the company’s AI research, but nothing has been heard of it in the three-and-a-half years since the acquisition. It remains a mystery who is on it, what they discuss, or even whether it has officially met.

The unit, called DeepMind Ethics and Society, is not the AI Ethics Board that DeepMind was promised when it agreed to be acquired by Google in 2014. That board, which was convened by January 2016, was supposed to oversee all of the company’s AI research, but nothing has been heard of it in the three-and-a-half years since the acquisition. It remains a mystery who is on it, what they discuss, or even whether it has officially met.

DeepMind Ethics and Society is also not the same as DeepMind Health’s Independent Review Panel, a third body set up by the company to provide ethical oversight – in this case, of its specific operations in healthcare.

Nor is the new research unit the Partnership on Artificial Intelligence to Benefit People and Society, an external group founded in part by DeepMind and chaired by the company’s co-founder Mustafa Suleyman. That partnership, which was also co-founded by Facebook, Amazon, IBM and Microsoft, exists to “conduct research, recommend best practices, and publish research under an open licence in areas such as ethics, fairness and inclusivity”.

Nonetheless, its creation is the hallmark of a change in attitude from DeepMind over the past year, which has seen the company reassess its previously closed and secretive outlook. It is still battling a wave of bad publicity started when it partnered with the Royal Free in secret, bringing the app Streams to active use in the London hospital without being open to the public about what data was being shared and how.

The research unit also reflects an urgency on the part of many AI practitioners to get ahead of growing concerns on the part of the public about how the new technology will shape the world around us.

Source: The Guardian

We believe AI can be of extraordinary benefit to the world, but only if held to the highest ethical standards.

Technology is not value neutral, and technologists must take responsibility for the ethical and social impact of their work.

Technology is not value neutral, and technologists must take responsibility for the ethical and social impact of their work.

As history attests, technological innovation in itself is no guarantee of broader social progress. The development of AI creates important and complex questions. Its impact on society—and on all our lives—is not something that should be left to chance. Beneficial outcomes and protections against harms must be actively fought for and built-in from the beginning. But in a field as complex as AI, this is easier said than done.

As scientists developing AI technologies, we have a responsibility to conduct and support open research and investigation into the wider implications of our work. At DeepMind, we start from the premise that all AI applications should remain under meaningful human control, and be used for socially beneficial purposes.

So today we’re launching a new research unit, DeepMind Ethics & Society, to complement our work in AI science and application. This new unit will help us explore and understand the real-world impacts of AI. It has a dual aim: to help technologists put ethics into practice, and to help society anticipate and direct the impact of AI so that it works for the benefit of all.

If AI technologies are to serve society, they must be shaped by society’s priorities and concerns.

Source: DeepMind

The missteps underscore how misinformation continues to undermine the credibility of Silicon Valley’s biggest companies.

The missteps underscore how misinformation continues to undermine the credibility of Silicon Valley’s biggest companies.

Accuracy matters in the moments after a tragedy. Facts can help catch the suspects, save lives and prevent a panic.

But in the aftermath of the deadly mass shooting in Las Vegas on Sunday, the world’s two biggest gateways for information, Google and Facebook, did nothing to quell criticism that they amplify fake news when they steer readers toward hoaxes and misinformation gathering momentum on fringe sites.

Google posted under its “top stories” conspiracy-laden links from 4chan — home to some of the internet’s most ardent trolls. It also promoted a now-deleted story from Gateway Pundit and served videos on YouTube of dubious origin.

The posts all had something in common: They identified the wrong assailant.

Facebook’s Crisis Response page, a hub for users to stay informed and mobilize during disasters, perpetuated the same rumors by linking to sites such as Alt-Right News and End Time Headlines, according to Fast Company.

The platforms have immense influence on what gets seen and read. More than two-thirds of Americans report getting at least some of their news from social media, according to the Pew Research Center. A separate global study published by Edelman last year found that more people trusted search engines (63%) for news and information than traditional media such as newspapers and television (58%).

Still, skepticism abounds that the companies beholden to shareholders are equipped to protect the public from misinformation and recognize the threat their platforms pose to democratic societies.

Source: LA Times

I was asking in the context of the aftermath of the 2016 election and the misinformation that companies like Facebook, Twitter, and Google were found to have spread.

I was asking in the context of the aftermath of the 2016 election and the misinformation that companies like Facebook, Twitter, and Google were found to have spread.

“I view it as a big responsibility to get it right,” he says. “I think we’ll be able to do these things better over time. But I think the answer to your question, the short answer and the only answer, is we feel huge responsibility.”

But it’s worth questioning whether Google’s systems are making the rightdecisions, even as they make some decisions much easier.

People are already skittish about how much Google knows about them, and they are unclear on how to manage their privacy settings. Pichai thinks that’s another one of those problems that AI could fix, “heuristically.”

“Down the line, the system can be much more sophisticated about understanding what is sensitive for users, because it understands context better,” Pichai says. “[It should be] treating health-related information very differently from looking for restaurants to eat with friends.” Instead of asking users to sift through a “giant list of checkboxes,” a user interface driven by AI could make it easier to manage.

Of course, what’s good for users versus what’s good for Google versus what’s good for the other business that rely on Google’s data is a tricky question. And it’s one that AI alone can’t solve. Google is responsible for those choices, whether they’re made by people or robots.

The amount of scrutiny companies like Facebook and Google — and Google’s YouTube division — face over presenting inaccurate or outright manipulative information is growing every day, and for good reason.

Pichai thinks that Google’s basic approach for search can also be used for surfacing good, trustworthy content in the feed. “We can still use the same core principles we use in ranking around authoritativeness, trust, reputation.

What he’s less sure about, however, is what to do beyond the realm of factual information — with genuine opinion: “I think the issue we all grapple with is how do you deal with the areas where people don’t agree or the subject areas get tougher?”

When it comes to presenting opinions on its feed, Pichai wonders if Google could “bring a better perspective, rather than just ranking alone. … Those are early areas of exploration for us, but I think we could do better there.”

Source: The Verge

John Giannandrea, who leads AI at Google, is worried about intelligent systems learning human prejudices.

… concerned about the danger that may be lurking inside the machine-learning algorithms used to make millions of decisions every minute.

The real safety question, if you want to call it that, is that if we give these systems biased data, they will be biased

The problem of bias in machine learning is likely to become more significant as the technology spreads to critical areas like medicine and law, and as more people without a deep technical understanding are tasked with deploying it. Some experts warn that algorithmic bias is already pervasive in many industries, and that almost no one is making an effort to identify or correct it.

Karrie Karahalios, a professor of computer science at the University of Illinois, presented research highlighting how tricky it can be to spot bias in even the most commonplace algorithms. Karahalios showed that users don’t generally understand how Facebook filters the posts shown in their news feed. While this might seem innocuous, it is a neat illustration of how difficult it is to interrogate an algorithm.

Facebook’s news feed algorithm can certainly shape the public perception of social interactions and even major news events. Other algorithms may already be subtly distorting the kinds of medical care a person receives, or how they get treated in the criminal justice system.

This is surely a lot more important than killer robots, at least for now.

Source: MIT Technology Review

“Personally, I think the idea that fake news on Facebook, it’s a very small amount of the content, influenced the election in any way is a pretty crazy idea.”

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s company recently said it would turn over to Congress more than 3,000 politically themed advertisements that were bought by suspected Russian operatives. (Eric Risberg/AP

Nine days after Facebook chief executive Mark Zuckerberg dismissed as “crazy” the idea that fake news on his company’s social network played a key role in the U.S. election, President Barack Obama pulled the youthful tech billionaire aside and delivered what he hoped would be a wake-up call.

Obama made a personal appeal to Zuckerberg to take the threat of fake news and political disinformation seriously. Unless Facebook and the government did more to address the threat, Obama warned, it would only get worse in the next presidential race.

“There’s been a systematic failure of responsibility. It’s rooted in their overconfidence that they know best, their naivete about how the world works, their extensive effort to avoid oversight, and their business model of having very few employees so that no one is minding the store.” Zeynep Tufekci

Zuckerberg acknowledged the problem posed by fake news. But he told Obama that those messages weren’t widespread on Facebook and that there was no easy remedy, according to people briefed on the exchange

One outcome of those efforts was Zuckerberg’s admission on Thursday that Facebook had indeed been manipulated and that the company would now turn over to Congress more than 3,000 politically themed advertisements that were bought by suspected Russian operatives.

These issues have forced Facebook and other Silicon Valley companies to weigh core values, including freedom of speech, against the problems created when malevolent actors use those same freedoms to pump messages of violence, hate and disinformation.

Congressional investigators say the disclosure only scratches the surface. One called Facebook’s discoveries thus far “the tip of the iceberg.” Nobody really knows how many accounts are out there and how to prevent more of them from being created to shape the next election — and turn American society against itself.

“There is no question that the idea that Silicon Valley is the darling of our markets and of our society — that sentiment is definitely turning,” said Tim O’Reilly, an adviser to tech executives and chief executive of the influential Silicon Valley-based publisher O’Reilly Media

Source: Washington Post

IBM Chairman, President, and Chief Executive Officer Ginni Rometty. PHOTOGRAPHER: STEPHANIE SINCLAIR FOR BLOOMBERG BUSINESSWEEK

If I considered the initials AI, I would have preferred augmented intelligence.

It’s the idea that each of us are going to need help on all important decisions.

A study said on average that a third of your decisions are really great decisions, a third are not optimal, and a third are just wrong. We’ve estimated the market is $2 billion for tools to make better decisions.

That’s what led us all to really calling it cognitive

“Look, we really think this is about man and machine, not man vs. machine. This is an era—really, an era that will play out for decades in front of us.”

We set out to build an AI platform for business.

AI would be vertical. You would train it to know medicine. You would train it to know underwriting of insurance. You would train it to know financial crimes. Train it to know oncology. Train it to know weather. And it isn’t just about billions of data points. In the regulatory world, there aren’t billions of data points. You need to train and interpret something with small amounts of data.

This is really another key point about professional AI. Doctors don’t want black-and-white answers, nor does any profession. If you’re a professional, my guess is when you interact with AI, you don’t want it to say, “Here is an answer.”

What a doctor wants is, “OK, give me the possible answers. Tell my why you believe it. Can I see the research, the evidence, the ‘percent confident’? What more would you like to know?”

It’s our responsibility if we build this stuff to guide it safely into the world.

Source: Bloomberg

PL – Looks like Siri needs more help to understand.

PL – Looks like Siri needs more help to understand.

“People have serious conversations with Siri. People talk to Siri about all kinds of things, including when they’re having a stressful day or have something serious on their mind. They turn to Siri in emergencies or when they want guidance on living a healthier life. Does improving Siri in these areas pique your interest?

Come work as part of the Siri Domains team and make a difference.

We are looking for people passionate about the power of data and have the skills to transform data to intelligent sources that will take Siri to next level. Someone with a combination of strong programming skills and a true team player who can collaborate with engineers in several technical areas. You will thrive in a fast-paced environment with rapidly changing priorities.”

The position requires a unique skill set. Basically, the company is looking for a computer scientist who knows algorithms and can write complex code, but also understands human interaction, has compassion, and communicates ably, preferably in more than one language. The role also promises a singular thrill: to “play a part in the next revolution in human-computer interaction.”

The job at Apple has been up since April, so maybe it’s turned out to be a tall order to fill. Still, it shouldn’t be impossible to find people who are interested in making machines more understanding. If it is, we should probably stop asking Siri such serious questions.

Computer scientists developing artificial intelligence have long debated what it means to be human and how to make machines more compassionate. Apart from the technical difficulties, the endeavor raises ethical dilemmas, as noted in the 2012 MIT Press book Robot Ethics: The Ethical and Social Implications of Robotics.

Even if machines could be made to feel for people, it’s not clear what feelings are the right ones to make a great and kind advisor and in what combinations. A sad machine is no good, perhaps, but a real happy machine is problematic, too.

In a chapter on creating compassionate artificial intelligence (pdf), sociologist, bioethicist, and Buddhist monk James Hughes writes:

Programming too high a level of positive emotion in an artificial mind, locking it into a heavenly state of self-gratification, would also deny it the capacity for empathy with other beings’ suffering, and the nagging awareness that there is a better state of mind.

Source: Quartz

PL – The challenge of an AI using Emotion Reading Tech just got dramatically more difficult.

A new study identifies 27 categories of emotion and shows how they blend together in our everyday experience.

Psychology once assumed that most human emotions fall within the universal categories of happiness, sadness, anger, surprise, fear, and disgust. But a new study from Greater Good Science Center faculty director Dacher Keltner suggests that there are at least 27 distinct emotions—and they are intimately connected with each other.

“We found that 27 distinct dimensions, not six, were necessary to account for the way hundreds of people reliably reported feeling in response to each video”

Moreover, in contrast to the notion that each emotional state is an island, the study found that “there are smooth gradients of emotion between, say, awe and peacefulness, horror and sadness, and amusement and adoration,” Keltner said.

“We don’t get finite clusters of emotions in the map because everything is interconnected,” said study lead author Alan Cowen, a doctoral student in neuroscience at UC Berkeley.

“Emotional experiences are so much richer and more nuanced than previously thought.”

Source: Mindful

…or the learned morals of an evolving algorithm. SAS CTO Oliver Schabenberger

With the advent of deep learning, machines are beginning to solve problems in a novel way: by writing the algorithms themselves.

The software developer who codifies a solution through programming logic is replaced by a data scientist who defines and trains a deep neural network.

The expert who studied and learned a domain is replaced by a reinforcement learning algorithm that discovers the rules of play from historical data.

We are learning incredible lessons in this process.

But does the rise of such highly sophisticated deep learning mean that machines will soon surpass their makers? They are surpassing us in reliability, accuracy and throughput. But they are not surpassing us in thinking or learning. Not with today’s technology.

The artificial intelligence systems of today learn from data – they learn only from data. These systems cannot grow beyond the limits of the data by creating, innovating or reasoning.

Even a reinforcement learning system that discovers rules of play from past data cannot develop completely new rules or new games. It can apply the rules in a novel and more efficient way, but it does not invent a new game. The machine that learned to play Go better than any human being does not know how to play Poker.

Where to from here?

True intelligence requires creativity, innovation, intuition, independent problem solving, self-awareness and sentience. The systems built based on deep learning do not – and cannot – have these characteristics. These are trained by top-down supervised methods.

We first tell the machine the ground truth, so that it can discover its regularities. They do not grow beyond that.

Source: InformationWeek

AI works, in part, because complex algorithms adeptly identify, remember, and relate data … Moreover, some machines can do what had been the exclusive domain of humans and other intelligent life: Learn on their own.

AI works, in part, because complex algorithms adeptly identify, remember, and relate data … Moreover, some machines can do what had been the exclusive domain of humans and other intelligent life: Learn on their own.

As a researcher schooled in scientific method and an ethicist immersed in moral decision-making, I know it’s challenging for humans to navigate concurrently the two disparate arenas.

It’s even harder to envision how computer algorithms can enable machines to act morally.

Moral choice, however, doesn’t ask whether an action will produce an effective outcome; it asks if it is a good decision. In other words, regardless of efficacy, is it the right thing to do?

Such analysis does not reflect an objective, data-driven decision but a subjective, judgment-based one.

Individuals often make moral decisions on the basis of principles like decency, fairness, honesty, and respect. To some extent, people learn those principles through formal study and reflection; however, the primary teacher is life experience, which includes personal practice and observation of others.

Placing manipulative ads before a marginally-qualified and emotionally vulnerable target market may be very effective for the mortgage company, but many people would challenge the promotion’s ethicality.

Humans can make that moral judgment, but how does a data-driven computer draw the same conclusion? Therein lies what should be a chief concern about AI.

Can computers be manufactured with a sense of decency?

Can coding incorporate fairness? Can algorithms learn respect?

It seems incredible for machines to emulate subjective, moral judgment, but if that potential exists, at least four critical issues must be resolved:

Source: Business Insider David Hagenbuch

SAN JOSE, CA – APRIL 18: Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg delivers the keynote address at Facebook’s F8 Developer Conference on April 18, 2017 at McEnery Convention Center in San Jose, California. (Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

… recent story in The Washington Post reported that “minority” groups feel unfairly censored by social media behemoth Facebook, for example, when using the platform for discussions about racial bias. At the same time, groups and individuals on the other end of the race spectrum are quickly being banned and ousted in a flash from various social media networks.

Most all of such activity begins with an algorithm, a set of computer code that, for all intents and purposes for this piece, is created to raise a red flag when certain speech is used on a site.

But from engineer mindset to tech limitation, just how much faith should we be placing in algorithms when it comes to the very sensitive area of digital speech and race, and what does the future hold?